This year I don’t have to deal with too many aggressive behaviors. This is a relief, although I realize that aggression is often part of the job when you teach students with classic autism. This year, the behavior that I have to manage is less aggressive and more annoying.

Now, sit down and try to write a social story about how you shouldn’t be annoying. You can’t. It’s impossible. There are an infinite number of ways to annoy anyone and the things that tickle the “I’m annoyed” center in the brain are different for different people.

I have one student in particular in mind as I write this post (I’ll call him Brian), and he breaks my heart. He breaks my heart because Brian can be oh-so-annoying but he is also the most social kid in my class. He adores his classmates and his typical peers and he wants so badly to have friends. Unfortunately, his social skills are atrocious.

He believes that if he is having fun, then everyone else is having fun. If he is laughing, then the other person must be enjoying the activity just as much as he is. As Brian kicks the bathroom door, he looks around at his peer as he laughs hysterically as if to say, ‘Aren’t we all having a blast?’. He presses the “Stop” button every chance he gets on another student’s AAC device because that student laughed. Once. In September.

These behaviors are attention-seeking in nature but he is genuine in his effort to establish a connection with peers and staff members. This makes it all the more difficult to see Brian continually face negative consequences (time outs, etc.) for these social efforts. It doesn’t seem to be true that he enjoys negative attention just as much as positive attention. In fact, he will often shut down for hours if he feels like he is ‘in trouble.’ He just doesn’t know the rules for establishing positive social connections.

I knew that I was missing an important piece in teaching this student to be more positively social, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. Most of my students have classic autism and managing an excess of social enthusiasm isn’t a common problem of mine.

Again, I had already attempted to write a social story about how Brian shouldn’t be annoying, and hadn’t had much luck. ‘Annoying’ is too hard to clearly define and is much too negative. My wheels were still spinning with ideas to shape Brian’s behavior when I reached my Structured Teaching PLC meeting.

At the meeting, two of my coworkers, Becky (@edgeSLP) and Charity, shared a strategy they had successfully implemented with other students. They had broken down Michelle Garcia Winner’s work in Think Social (2005) in order to teach students with moderate-significant cognitive impairments how their behavior affects others.

After listening to an overview of how Becky and Charity implemented a system with some of their students, I used their ideas and inspiration to complete the following:

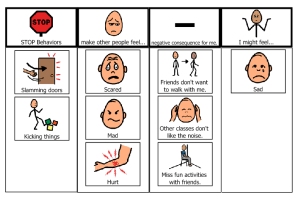

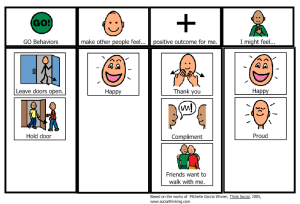

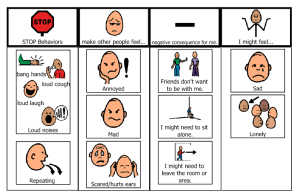

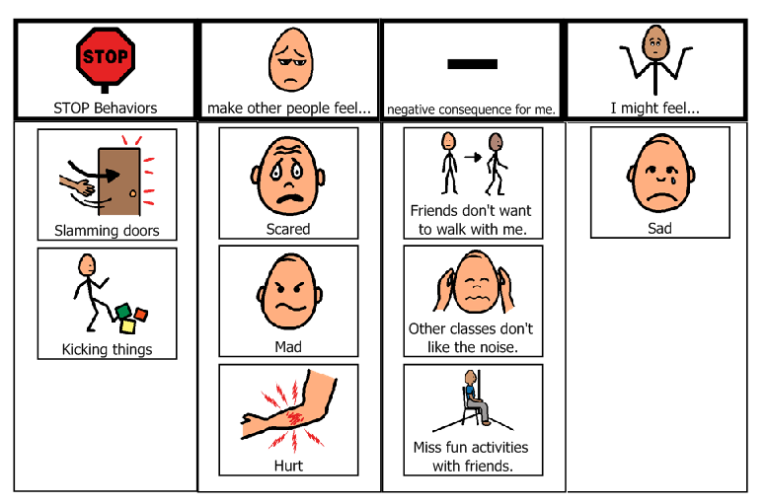

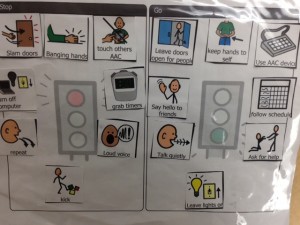

- Identify behaviors—For about a week, I kept a chart on the door to our classroom with two columns labeled ‘Stop’ and ‘Go.’ As we moved through our regular days, classroom staff (paraprofessionals, related service staff, etc.) filled the chart with behaviors we wanted to see stop and other behaviors we wanted to see more of. For one example, with Brian we wanted to see Brian do less door-slamming and more door-holding for other people. After the week was up, we had a significant list of things we wanted Brian to stop and other behaviors we wanted to see more of. It seemed to me that a week was a good length of time to identify behaviors—remember, most of these behaviors weren’t significant enough to warrant a true functional behavior assessment. They were just things that were irritating and were harder to pin down.

- Condense behaviors—After we collaboratively created a list of ‘Stop’ and ‘Go’ behaviors, I condensed them down by grouping similar behaviors together and scrapping the behaviors that I didn’t think were very important or I thought would be impossible to extinguish. For example, touching/grabbing things that didn’t belong to the student were defined as one behavior rather than identifying each thing the student touched/grabbed. I scrapped the behavior of Brian approaching kids he doesn’t know in the hallway and making a funny face—it is too difficult to control how peers react (they mostly laugh, thus reinforcing the behavior) and I didn’t think we would be successful with stopping that one.

- Sort Behaviors (Stop and Go)—Next, I used Boardmaker software to create an activity in which Brian sorted his behaviors into Stop and Go categories. I worked 1:1 with him during this activity, describing each behavior as we worked. Brian did fairly well the first time, but made 1-2 errors. We worked on this task together several times until he had mastered sorting the behaviors into ‘Stop’ and ‘Go’ categories.

- Create contingency maps—Once Brian understood the language and symbols I was using to describe the behaviors, I worked 1:1 with him to create contingency maps addressing the behaviors. I always tried to work on both a Stop map and a Go map during one session, and some maps addressed several related behaviors. I wanted Brian to see that were things that bothered others but there are just as many alternatives that would make other people happy and want to spend more time with him. During these sessions, Brian would occasionally get pretty down on himself. I could tell that it caused him some distress to see that some of his actions might make other people feel sad or not want to spend time with him.

- Video model the contingency maps—Optional. I’m not doing this with Brian, but I can see how this would be a valuable teaching tool for students with autism.

- Use teachable moments—At every opportunity, label the behavior, review the maps, and emphasize how others are feeling at those moments. Have typical peers and staff members exaggerate their reactions so their emotions are clear to the student. Review the contingency map if time/space allows. Sometimes Brian needs to take five minutes alone if he feels like he is being particularly hilarious in order to calm down before the review of the contingency map becomes meaningful. We emphasize to Brian that this is not a punishment, but he just needs to calm his body down so he is ready to listen and learn.

I have already seen positive changes in Brian’s behavior after implementing these strategies. In fact, Brian came in this morning and independently studied his behavior maps before getting started on his morning work. The maps are organized in a binder that travels with Brian throughout his day. We are praising the heck out of him whenever he does one of his ‘Go’ behaviors and choosing to teach rather than reprimand when he uses a ‘Stop’ behavior.

This has taken a lot of time, but I think overall it has been well worth it. I think we are addressing the root of his social problems rather than making him follow rules he doesn’t understand and that only apply in the classroom setting.

Thanks for reading! Please share other strategies you have used to help address student behavior that is related to social deficits!

Thanks for the detailed information. I’ve just started using this with my preschool/kindy children 3years 3 months to 5 years as some of them have come to the room with poor development of social skills an outcome of busy lives of parents. Eat, sleep, daycare/work, repeat. There also may be a few on the spectrum I suspect and we are documenting this for parents.

LikeLike